Identifying Willows on Yellowstone's Northern Range.

By Mike Tercek and Lorna McIntyre

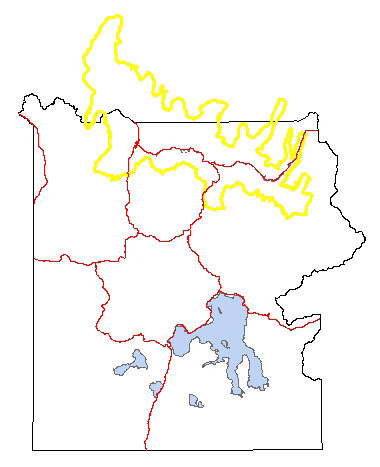

Map showing the boundary of Yellowstone's northern range (yellow). The northernmost point of this area is located near Tom Miner Basin in Paradise Valley. The black line delineates the boundary of Yellowstone National Park. Red lines are roads. |

For many years, scientists believed that Yellowstone's northern range (See map) was overgrazed. Riparian willows, cottonwoods, and aspen had been in decline since the 1920s. In some areas, these plants disappeared entirely, while in others dense thickets three meters tall were browsed down to less than waist high.

In the mid-1990s, riparian plants on the northern range began to recover. Some scientists now believe that this was due to a "top-down trophic cascade" in which wolves, which were reintroduced in 1995 - 1996, scare elk out of certain areas, reducing browsing rates and allowing the plants to grow taller. Other explanations might include a lengthening of the growing season due to climate change or changes in the hydrologic regime of small streams. Click here for more information on these alternative explanations. The northern range is officially defined as the area occupied by Yellowstone's northern elk herd during the winter. (map, left) It covers approximately 378,000 acres (153,000 hectares). Is the elk herd too large for this area? Are the plants in this area being overgrazed? How much have they recovered since 1996? These questions are not of merely scientific interest. The answers affect economically important policy considerations such as hunting limits and grazing rights outside the park; and terms such as "overgrazing" can be defined very differently by each interest group. |

For the reasons just mentioned, a number of researchers and resource managers are interested in knowing where willows occur on the northern range and how tall they are. Without this basic information, it would be difficult to track changes due to browsing (or wolf activity) in the coming decades.

We have recently completed a six year mapping and inventory effort of riparian willow on Yellowstone's Northern Range. You can download the final report for that project here. In the course of this project, we compiled pictures of the most common willow species and assembled notes on the distinguishing characteristics of each. This information has helped us in our field work, and you may find that it helps you confirm an identification that you have made in the field.

Sometimes, we still refer to the dichotomous keys found in the books listed below. These books are the definitive source of species identifications.

Dorn, R.D. 2003. Vascular Plants of Wyoming, Third Edition. Illustrations by J.L. Dorn. Mountain West Publishing, Cheyenne Wyoming. (A text-based flora with hand-drawn illustrations).

Dorn, R.D. 1997. Rocky Mountain Region Willow Identification Field Guide. Ilustrations by J.L. Dorn. USDA Forest Service Agr. Handbook No. 410. (Contains many photographs).

For a quick, but possibly not always as accurate, identification, you might try the dichotomous key composed by Jennifer Whipple, National Park Service botanist in Yellowstone. Click here to see the key.

Click on the name of a species in the list below to see pictures of it.

Salix exigua / Salix melanopsis (“Coyote willow” or "Sandbar willow"/ “Dusky willow”) – In some sites, these species can be distinguished easily, but we have found intermediates that completely span the range between the two species. Since they appear to hybridize with each other, we have grouped them together here. Both species seem to occur most often in disturbed habitats such as stream margins and gravel bars, and animals seem to browse them in preference to other willow species. When these species appear in a mixed community they are often the shortest and most heavily browsed.

Salix boothii -- Often found in wetter areas such as swamps or directly in streams. Leaves are equally green on both sides.

Salix drummondiana (“Drummond willow”) – Stems may or may not be pruinose (have a whitish-waxy coating that can easily be rubbed off). Focus on looking for stouter stems and slightly re-curved leaf margins. Under the magnifier, the hairs on the underside of the leaves are kinky. Usually found along creeks but NOT on benches or at the base of seeps such as Crystal Creek.

Salix geyeriana (“Geyer willow”) – Common on Blacktail Plateau. Less common on the Soda Butte Creek drainage. Typically not found in disturbed areas, but in wetter or poorly drained sites. Twigs pruinose. Narrow, linear leaves. No stipules. Usually hairy on both sides of leaf. Leaves are light minty green.

Salix lemmonii (“Lemmon willow”) – Leaves are more two-toned than S. geyeriana. Upper leaf surface usually more glabrous than S.geyeriana. Catkin bracts are black and round rather than tan and oval as in S. geyeriana.

Salix bebbiana (“Bebb willow”) –Usually found in wetter or swampy sites. If not browsed, often takes on a dumb-bell – shaped growth form as it reaches maturity. Older stems have grey mottling on bark. Characteristic imprinted leaf venation best seen from the underside of leaf and leaf veins often hairy. Topside of leaves are leathery. Catkins have unusually long stipes.

Salix pseudomonticola (“Serviceberry willow”) – Leaves wider than S. bebbiana and often have a red mid-vein. Upper surface of leaf not as shiny as S. planifolia. For comparison to S. bebbiana, look at underside of leaf: imprinted venation is obvious in S. bebbiana but not present in this species. Leaf margins are broadly serrate when compared to S. eriocephala var. watsonii, which has finely serrated leaf margins.

Salix eriocephala var. watsonii (“Yellow willow”) – Looks like S. boothii but has two-tone leaves with glacous (waxy) undersides, while S. boothii has leaves that are equally green on both sides. Differs from S. pseudomonticola in NOT having red leaf mid-veins and has finely serrated leaf margins. Bark is smooth and grey, like a young cottonwood sapling. Young cottonwood saplings can be mistaken for this species, but cottonwood saplings lack conspicuous stipules and their leaves seem to be thicker than this willow.

Salix lasiandra (“Longleaf willow”) - Leaves are not two-toned and glabrous. Leaf shape is generally egg-shaped with a long and pointy tip. The best characteristic is the glands located at the base of the leaf near petiole (glands on this species are larger than the glands of S. eastwoodii).

Salix wolfii (“Wolf willow”) – Leaves are often hairy on both sides. Likes drier sites near the edges of meadows or upslope from wetlands. Usually shorter. Rarely taller than 150cm.

Salix eastwoodii (Eastwood willow”) – Looks a lot like S. wolfii but often taller and has wider leaves that are often obovate. Often has small glands on the lower margin of the leaf blade. We rarely saw this species in YNP's northern range.

Salix candida (“Hoary willow”) – Very hairy leaves, especially the underside of leaf. Stems are wooly. There a high density of this willow behind Floating Island Lake.

Salix planifolia - Characteristic shiny to oily leaves and stems.

Salix farriae (“Farr willow”) – A low shrub with spreading, drooping branches. Leaves look like S. bebbiana but are softer and veinier on the underside. Small catkins. On Soda Butte Creek near Cooke City and Silver Gate. Also on Swan Lake Flats.

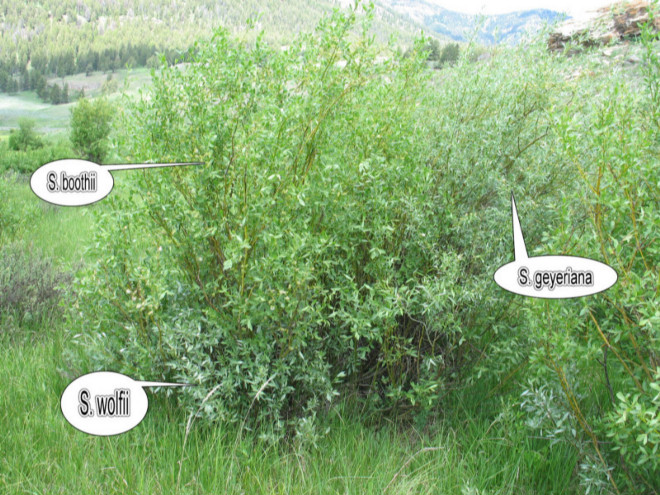

Willows species often grow quite closely together. The picture below shows a typical situation, in which three different species are intermingled in a single thicket.